Read What Makes You Happy. Or Don't.

On media literacy, thinking critically, and how we can all do a little bit better.

For many, reading functions as a form of escapism from the drudgery and woes of everyday life, particularly on the heels of an earth-shattering pandemic and in the face of rising fascism. We could all certainly use a bit of a breather from…*gestures broadly.* But does that mean that reading should always be a mindlessly entertaining activity?

With the rise of bookish social media communities, including but not limited to Bookstagram and BookTok, it’s easier than ever for readers to share their opinions about books on the World Wide Web—for better or for worse. And in this ever-expanding universe of book reviews, it’s increasingly apparent that many people are unwilling (or even unable) to engage with books critically. Many readers, fed up with a character’s poor choices or general un-likability, label a book as “bad” or “poorly written.” Others, troubled by the mere presence of a conflict such as racism, sexism, homophobia, or classism, jump to label the book as “problematic.”

Similarly, there are many readers out there who balk at the idea of reading books with a critical eye, leaning on the tired phrase “it’s not that serious” or “it’s just a book.” But this sort of flimsy, hasty literary engagement ignores the work and goals of the author, the significance of plot/character devices, and the broader role of literature within society.

On the pervasive lack of media literacy, one Twitter user (@koviebiakolo) writes:

we don’t talk enough about how reading is a SKILL. we make jokes about people not reading but there are people who do read but don’t read WELL. it’s why Reading Comprehension is a class in grade/elementary/primary school. it is simply not enough to be technically literate.

In response, Tressie McMillan Cottom (@tressiemcphd), author of Thick, notes:

. . . People do not read well. They cannot discern sentiment. They cannot draw conclusions. They cannot compare texts. And we are now past being in a discourse society. We are in a manipulated discourse society. Recipe for disaster.

In our quest to find solace in books, many of us have reduced the role of literature to something that should always make us happy, be quick and easy to understand, and/or reaffirm our understanding of the world around us. In other words, many folks are exclusively looking for Hallmark movie-level literary fluff that requires relatively little brain power but is nevertheless emotionally rewarding. Although this is not always necessarily a bad thing, and there are many books out there that are meant to and do make us happy without requiring too much thought, there are just as many books out there that are meant to challenge our understanding of the world, explore underrepresented experiences, and consider the complexity of humanity. The trouble comes when we as readers expect every book to make us feel warm and fuzzy, and require virtually no mental work. And issues further arise when we as readers push back against any suggestion from others that a book contains more substance than we initially thought.

At the risk of sounding like a crotchety old lady (aren’t I one, though?), I tend to believe that the rise of on-demand, easily binge-able entertainment (e.g., Netflix) has made many of us believe that media, including books, is something meant to be consumed primarily for entertainment value. People are reading books, but many times we are taking a consumerist, flattened approach to how we engage with literature. So…what to do?

Is the book Bad, or is it…

If you’ve been in any bookish online community for any amount of time, you’ve probably stumbled upon negative reviews of books that rest on at least one of the following overarching complaints:

“I just couldn’t relate to/like any of the characters.”

The relatability “critique” is most often lobbed by white readers who have at almost every turn seen themselves and their experiences represented in media, and thus find it virtually impossible to connect with a book on any level if the main character is not white. While Black, Indigenous, and other readers of color are constantly forced to relate to white people to succeed at work, school, or other aspects of our daily lives, the reverse is rarely if ever demanded from our white counterparts. Until very recently, it was exceedingly difficult for young children of color to find books centering characters who looked like us, and as a result, many of us spent our formative years connecting to people with vastly different life experiences. And even today, when there are increasing (but still disproportionately low) numbers of popular books by authors of color, such authors are often expected to cater to white western readers by translating basic non-English phrases or inserting explanatory commas every few pages.

Beyond the ways in which this criticism is rooted in white normativity and supremacy, complaints about “relatability” beg the question: why do we read? Do we read to see our own peculiar experiences reflected back to us? To have our own thoughts and beliefs validated? To easily insert ourselves into new situations?

Reading is less an insular, individual experience and more a conversation between at least two parties: the author and the reader. When we rate a book poorly simply because it “isn’t relatable,” we are saying that we are unwilling to engage with the work the author is doing because it requires us to step beyond the threshold of our own lived experiences. We are saying that we want a dialogue to instead be a monologue. And that should give us pause.

This bleeds into a related complaint that a book was Bad because the character was [annoying/unsympathetic/prone to making poor choices]. And I get it—I really do! People in the real world are exhausting enough, so why do fictional people have to be tiresome too? But demanding that books present only likable characters who almost always make good life decisions requires authors to flatten the complexities of human experiences into some sort of alternate reality where people are mostly agreeable, conflicts are present but not too acrimonious, and everyone generally winds up happy in the end. Everyone of course needs a few books in their lives like this, but suggesting that a book is Bad simply because there is “no one to root for” is akin to punishing a book for being too lifelike.

One of the beauties of literature is the ways in which it empowers people to examine the nuances of the human experience, and why it’s so important to have fleshed out, well-developed characters (we’ll save that discussion for a different day). That means that not everyone will always make choices you agree with, some characters will get on your nerves, and sometimes there will be people you straight up hate in a book. That doesn’t necessarily make the book Bad—more interesting, perhaps.

“This book is problematic because [character] said/did something racist/homophobic/misogynistic.”

Admittedly, this can be a tough one, but it’s something I’ve seen increasingly in younger readers, particularly on BookTok. It goes without saying that there are absolutely books out there that traffic in harmful and violent stereotypes, tropes, and narratives. We are still very much in an environment in which racism, antisemitism, Islamophobia, homophobia, transphobia, and sexism run rampant through the media and society more broadly. But, because of this, there are also books in which the author is attempting to speak to these issues either through a plot arc or through an individual character. The question of whether a book is harmful shouldn't be just whether there is a troubling character or plot point in a book, but what the author is seeking to achieve through that character or plot point—and to what extent the author achieves that goal.

The question is not just whether you feel discomfort at the conflicts in the book, but what, if anything, the author is asking the reader to do with that discomfort. An author is not necessarily the characters they animate, and not every conflict in a book suggests that the book itself is perpetuating racism, homophobia, sexism, or other manifestations of bigotry. A book with a police brutality scene is not necessarily pro-police brutality! However, if the author has characters who engage in bigotry without any consequences, in-text third-party criticism, or out-of-text author engagement that examines the issues with said characters’ actions, that’s…probably a red flag.

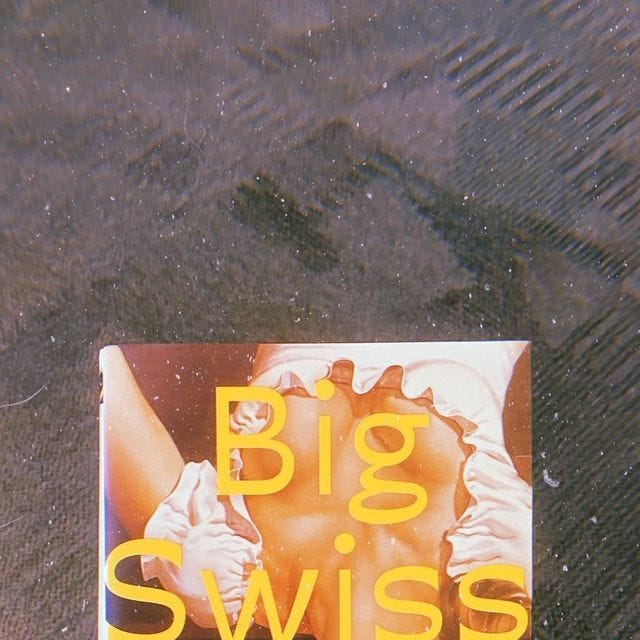

One of my favorite people on Bookstagram, @janandthings, highlighted the countless issues in Jen Beagin’s Big Swiss, chief of which was Beagin’s “mask[ing] her discomfort with trauma (and people of colour) through the guise of satire. . . . [the main character]’s racism is never painted as a main character flaw.” Rather than examining the character’s racism, Beagin continually and uncritically places people of color at the butt of jokes. Beagin’s goal of examining trauma responses falls flat because it fails to adequately address and explore the character’s horrific patterns of racism.

You should also check out Janelle’s amazing post on the issues with the genre of so-called “unhinged woman”—it’s absolutely worth a read and speaks to a lot of these same media literacy-related issues. She aptly points out the ways in which many people, in the interest of reading an entertaining book about an “unhinged” main character, neglect (or don’t care) to think critically about how such tropes perpetuate many forms of bigotry.

Some books that I think are great examples of works in which authors thoughtfully explore discrimination, identity, and other related issues, sometimes by generating discomfort in the reader:

A History of Burning by Janika Oza

The Trees by Percival Everett

Disorientation by Elaine Hsieh Chou

On Beauty by Zadie Smith

Ok, but now you’re making reading boring and tedious. If I wanted to do all that I’d just go back to school.

Well!!! None of this is to say that we should all take something that is a hobby, something that helps us cope amidst never-ending toils within late capitalist society, and turn it into some kind of heavily academic endeavor. What I am suggesting, however, is that we all think a bit more critically about how we engage with media. It can be hard! But it’s also immensely rewarding—by having more thoughtful dialogue with authors, by stretching those brain muscles a bit more, we can expand our understanding of the work, the author, and even the world around us. And that’s something worth exploring even if it means that not every book we read will be the mindless escapism we’re yearning for.

While we’re on the topic of book reviews, here’s some other reviewers that I think have some great, nuanced discussions of diverse literary works:

And, for further reading on this and related issues, check out:

Playing in the Dark by Toni Morrison

How to Read Now by Elaine Castillo

The Banality of Empathy by Namwali Serpell

Do you have thoughts on media literacy/critical thinking? Drop ‘em in the comments—let’s chat!

*Gestures broadly* 😂🙌

Points were made! Really appreciated reading your thoughts here and thank you for the mention!